All Set for the West: Railroads and the National Parks

2016 marked the centennial of National Park Service. Created by Act of Congress on August 25, 1916, its stated goal was:

“to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life [sic] and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Those who worked to create the National Park Service found willing partners in the nation's railroads. In the golden age of rail travel, when people rushed to see what they considered to be a vanishing frontier, Union Pacific and other railroads worked to preserve that landscape for their passengers. When that goal finally became a reality, a mutually beneficial relationship began that persevered from 1916 through most of the twentieth century.

“The Only Place in the World Where the Reality Exceeds by a Hundred Fold the Advertisements, the Photographs, the Literature.” —A Visitor to the National Parks, c1930

What Did the West Mean for America?

In 1890, Congress declared the frontier closed-there was no more available land in the West. Americans were deeply affected. If the West was "conquered," what did it mean to be an American? What should the country do with the remaining wilderness? Americans began to feel nostalgic about the past. At the same time the Conservationist Movement, dedicated to saving wilderness, grew in popularity and the government began setting aside parcels of land as designated national parks. Paradoxically the government's policy towards indigenous populations still living in these areas was one of removal and cultural assimilation beginning in the early 19th Century and continuing during this period with the 1867 Indian Peace Commission. All formal treaty activities were suspended by 1871, and by 1900, 56 of 162 federal reservations had been established by executive order alone.

Railroads quickly realized the beautiful scenery along their passenger routes could be used as a selling point. Destination travel became a key marketing strategy in a country where riding the train was more than just a route from point A to point B. Union Pacific, among other railroads, began to encourage its passengers to enjoy the landscape outside their windows in the late 1890s, marketing itself as the "World's Pictorial Line." In 1903, Union Pacific began advertising trips to Yellowstone National Park and extended its Oregon Short Line right up to the western Yellowstone entrance in 1908.

Creating a “National Parks Bureau”

Union Pacific was not the only railroad to value natural landscapes. In 1872, Northern Pacific Railway and others successfully lobbied Congress for the creation of Yellowstone National Park. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe began development of Grand Canyon's South Rim in 1901 and Great Northern Railway served Glacier National Park beginning in 1910.

At the turn of the century, all railroads agreed to abolish billboards along their passenger lines to provide unobstructed views of the landscape.

However, the government structure in place to govern these new parks was a bureaucratic nightmare for the railroads. Any railroad seeking to extend a line to a national park had to run a gauntlet of negotiation with several different organizations such as the Department of the Interior, the Indian Office, the General Land Office, the Bureau of Mines, the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Forest Service. The railroads began pressing legislators to unite the leadership of the parks under one “bureau.” In 1911, at the first National Park Conference held in Yellowstone, representatives from every principal railroad endorsed the idea of consolidation.

At the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915, the railroads made their biggest contribution to the creation of the National Park Service. Held in San Francisco, the exposition was supposed to celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal, but the railroads used it instead to promote the National Parks. Each railroad built massive exhibits showcasing the parks they served with acres of recreational landscapes. Both the Union Pacific and Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) built elaborate exhibits promoting current national parks’ interests to the tune of $500,000 each. The AT&SF’s Grand Canyon exhibit led directly to its adoption as a national park in 1919. Union Pacific built a massive four and-a-half acre replica of Yellowstone National Park, complete with working geysers that spewed boiling water. This model also included a replica of the Old Faithful Inn with its dining hall and auditorium. The $500,000 contributed by UP and AT&SF was well over twice what Northern Pacific spent to build the original lodge in 1904.

Railroads were one part of a multi-pronged effort to create the National Park Service. Conservationists banded together, creating groups like American Civic Association, Camp Fire Club, Save the Redwoods League, Wilderness Society and Sierra Club, founded by famous conservationist John Muir. Between the Panama-Pacific International Exposition displays and future NPS Directors Stephen Mather and Horace Albright's cross-country speaking tour, “What Makes a National Park?” the creation of the National Park Service was assured.

A Foundational Relationship

After it was founded in 1916, the fledgling National Park Service needed help. The traditional police force of the national parks, the United States Army, vacated in 1918. The park rangers now had to work full time to keep out squatters, poachers and cattle ranchers. They had almost no resources to devote to visitors or even to park development. This was largely left to the railroads who built roads, cabins, hotels and provided concessions. Union Pacific provided access to national parks otherwise virtually impossible to visit easily like Zion, the North Rim of Grand Canyon and Death Valley National Monument. Union Pacific worked hand-in-hand with the National Park Service, managing concessions and visitor-related infrastructure in several National Parks in a foundational relationship that lasted more than half a century.

The Conservationist Movement and the Railroads

A railroad, by its nature, leaves a light footprint on the environment. Today we would call it “sustainable.” One hundred years ago, it was just good business. An efficient passenger line made as few stops as possible, preventing roadside development. This led to a virtually litter-free route into the parks. Since building a railroad was all about keeping costs low, cuts and fills were avoided whenever possible and railroads clung to the natural contours of the terrain. Atmosphere and scenic beauty was also important. Railroads worked hard to make sure that the view outside the passenger car windows was as pleasing to the eye as possible.

Pictures from the World's Pictorial Line

Right from the very beginning, visitors enjoyed having their pictures taken in the national parks. Throughout the 1920s, Union Pacific's entire Photographic Division was staffed by three men—Eyre Powell, Jack Bristol and Vincent H. Hunter. There was no separation of labor among Union Pacific photographers in those days—all three took photos, developed film, wrote articles for the monthly “Union Pacific Magazine” and even created movies on 16mm. The trio was joined at the end of the decade by photographer William A. Coons. The photos reproduced here were taken inside the national parks during the 1920s and 1930s.

The Nation’s First Peoples

It was no coincidence that the newly created National Park Service (NPS) was placed under the Department of the Interior. This large and complex bureaucratic department was also home to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. From the beginning there existed a tenuous relationship between the NPS and indigenous tribes that had been relocated, and in many cases forcibly evicted, from the newly established governmental areas. Despite this, there was a national momentum to preserve what was perceived as “vanishing” attributes of the American West: the unblemished natural landscape and the American Indian way of life.

Tribes continuing to live near the newly created parks were involved in varying degrees depending on the park as the new relationships evolved.

At the same time, American’s thirst for exploration and the unknown filled the curio shops at several major parks with Tribal cultural merchandise for sale and demonstrations of cultural practices like weaving. This also included participation at major park events. For example, when Zion National Park was opened on June 1, 1925, Union Pacific invited members of the Paiute Tribe to preside over the ceremony. Some parks employed members of nearby tribes, but true collaboration remained only cursory until the latter half of the 20thCentury.

Currently the National Parks Service works to integrate Native Peoples’ perspectives and voice in the interpretation of the parks. For example, this statement is proudly posted at the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trails Center in Omaha, Neb. "The Trail is committed to building true relations with all people, to learn from them and to tell their stories with sensitivity and respect while working to preserve and protect our natural and cultural heritage for future generations."

“Parkitecture”

Gilbert Stanley Underwood was a famous architect who designed buildings for Union Pacific Railroad and the national parks. Some of these buildings were huge places where people could meet, eat and tell stories. These were called lodges.

When Underwood designed a lodge, he used the trees and stones he found in the local area so that the lodge would match the environment. This type of architecture is called the National Park Service Rustic Style.

-

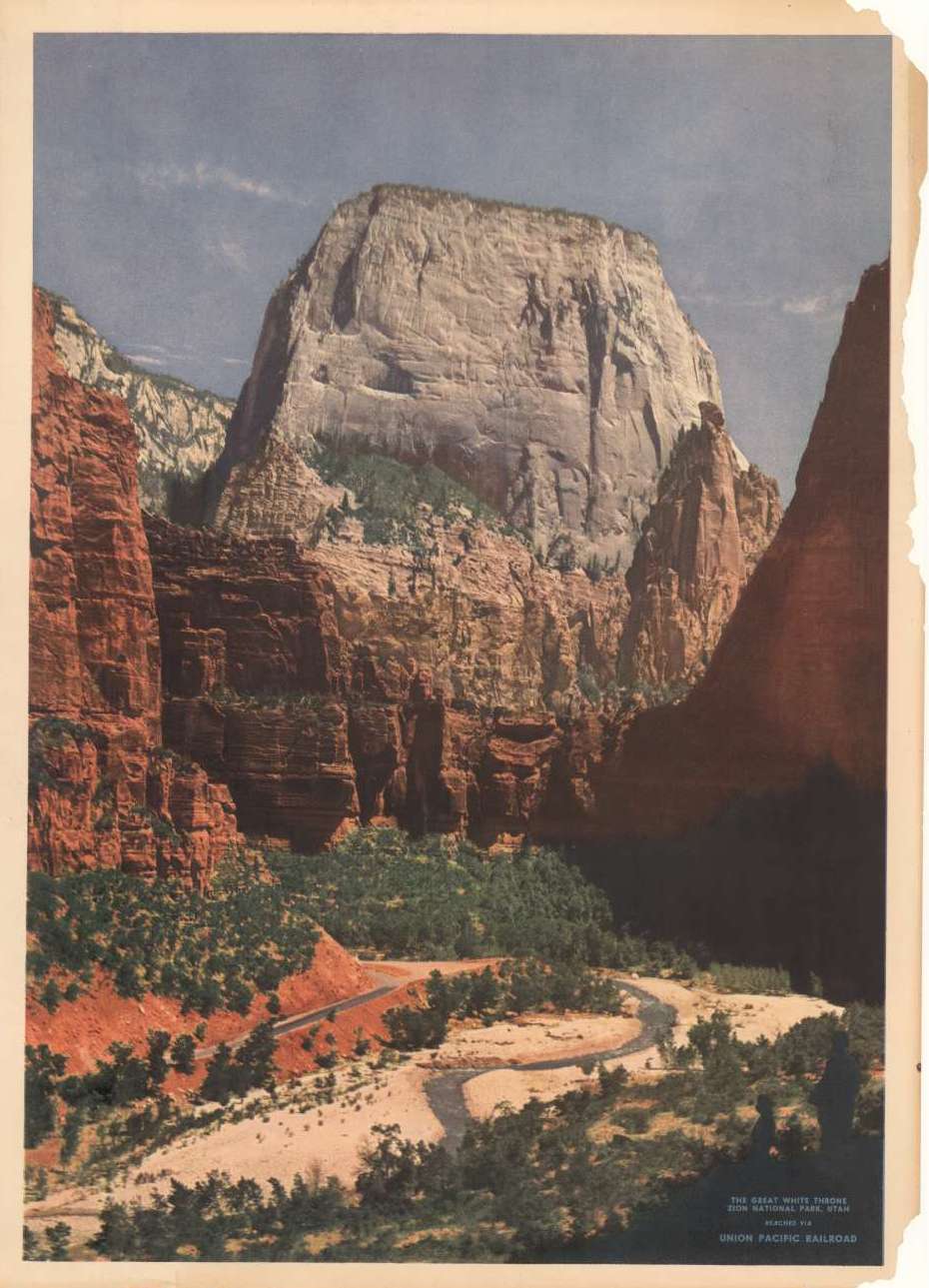

Cover of promotional brochure featuring the Great White Throne at Zion National Park, c1938, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

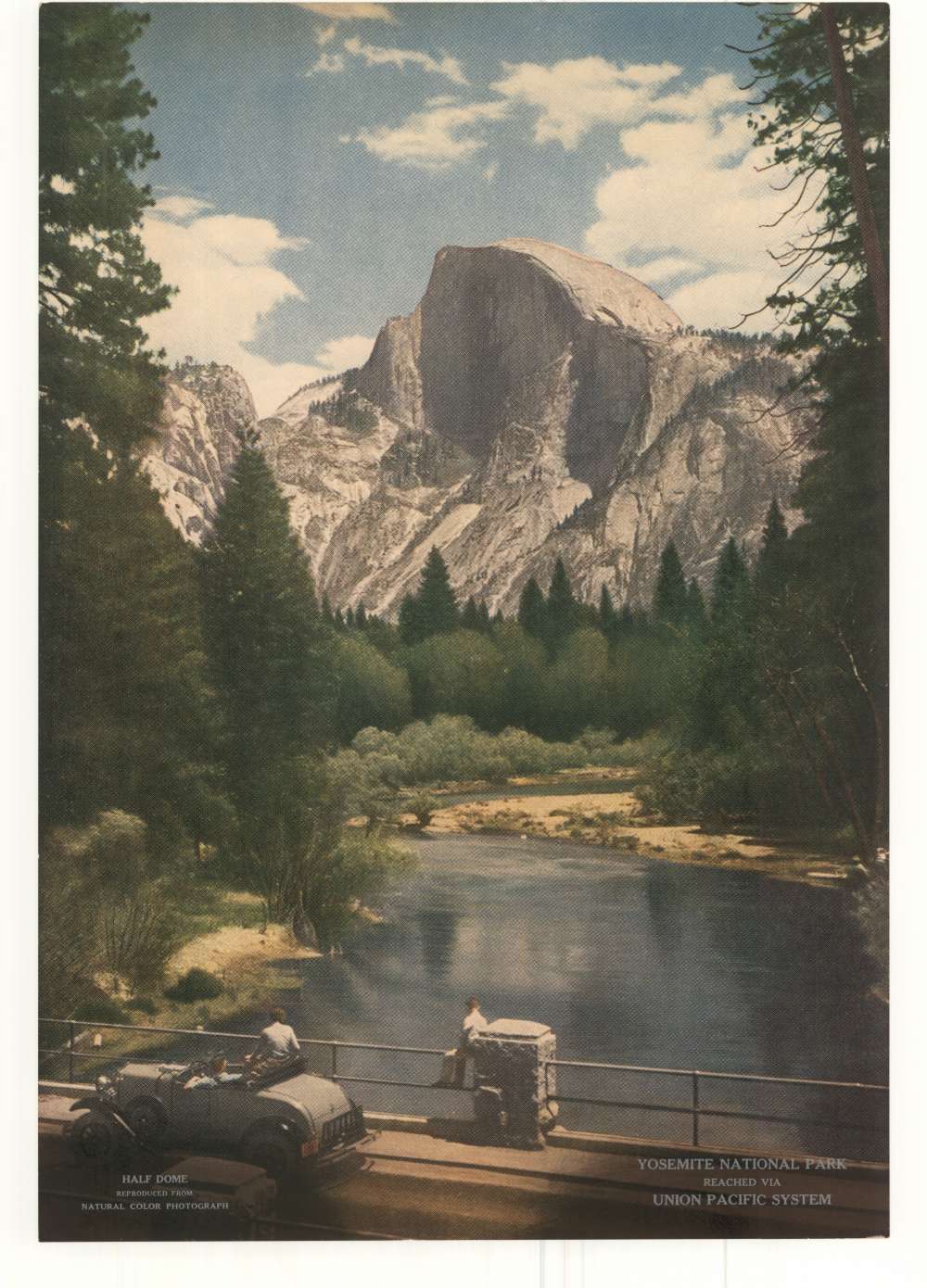

Promotional poster featuring the Half Dome rock formation at Yosemite National Park, California, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

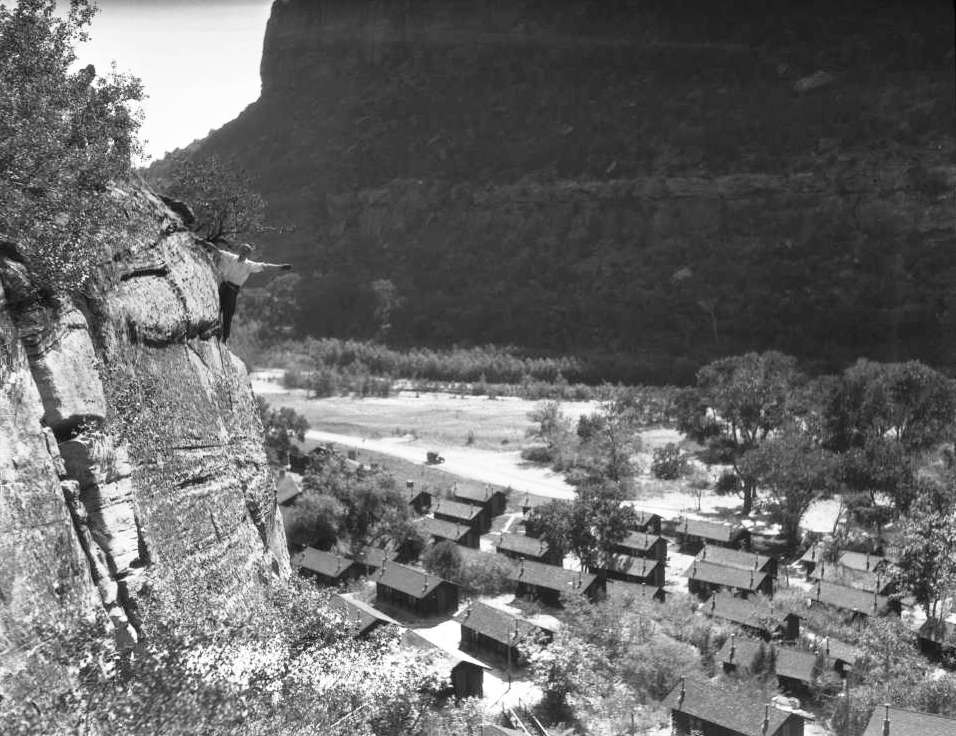

Vincent H. Hunter, Union Pacific photographer, points toward cabins and the lodge in Zion National Park, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

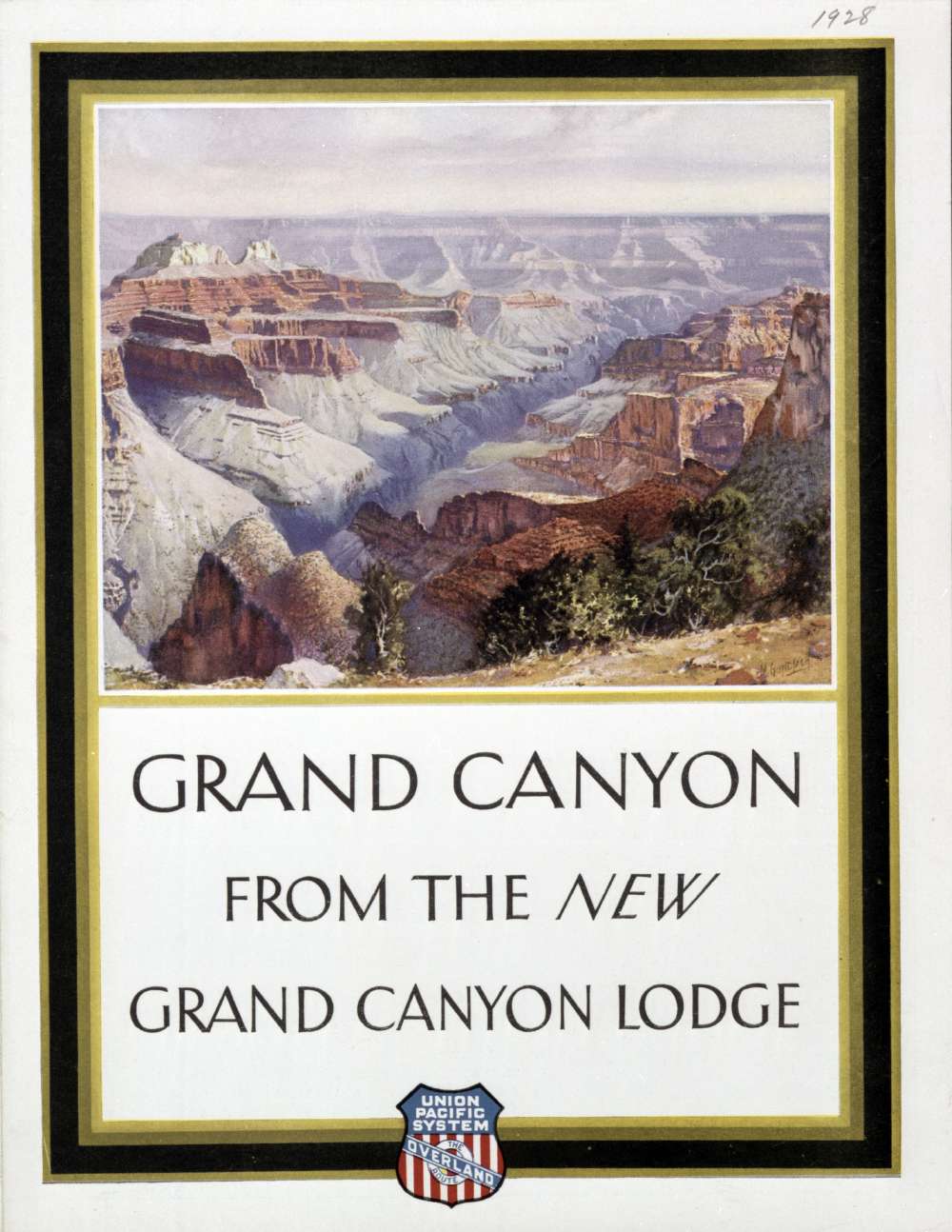

1928 Union Pacific Railroad Overland Route brochure, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

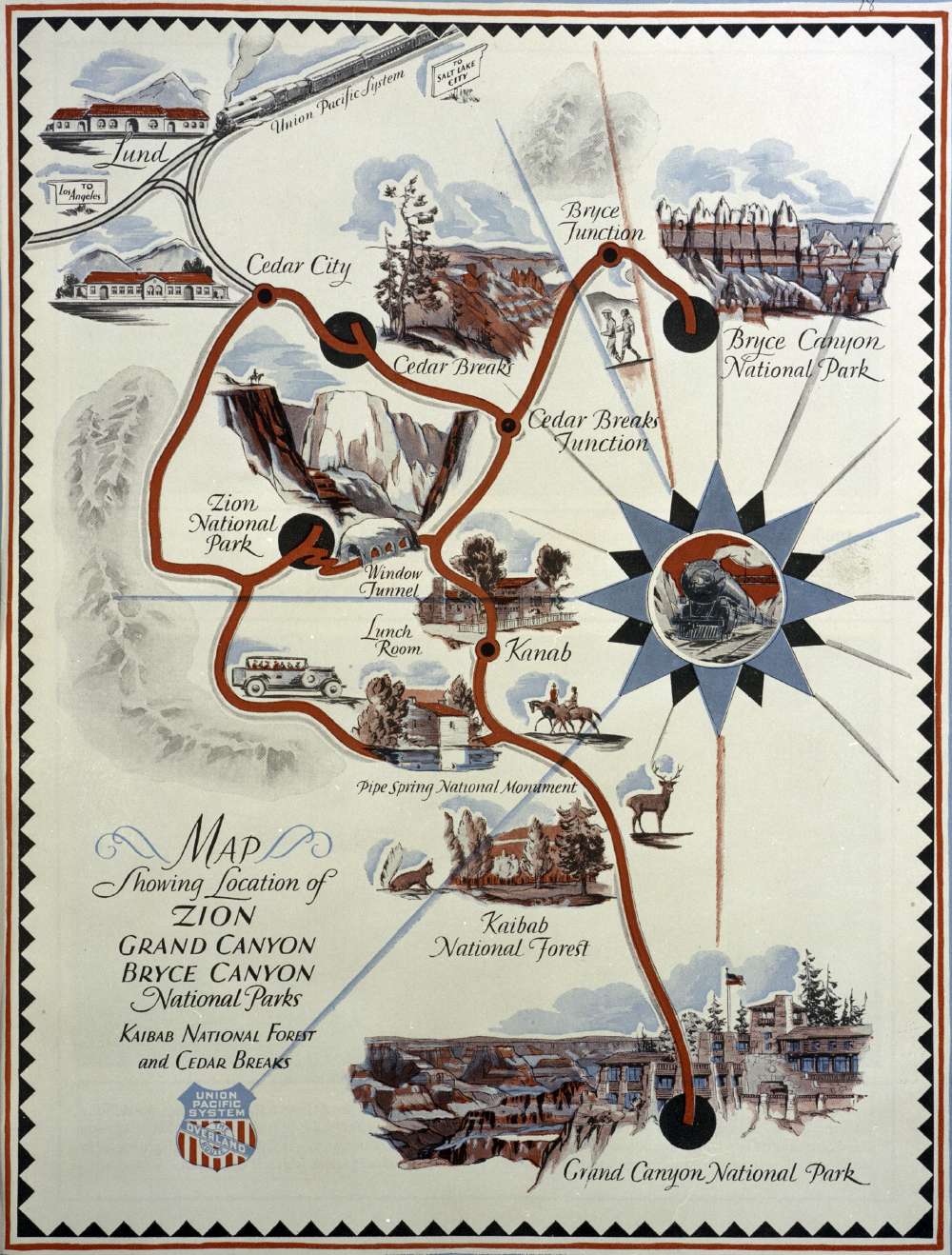

Hand-drawn 1920s map showing the locations of Zion, Grand Canyon, and Bryce Canyon National Parks along with the Kaibab National Forest and Cedar Breaks National Monument, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

![[A park ranger assists visitors at a Bryce Canyon National Park checkpoint, Union Pacific Museum Collection.] A park ranger assists visitors at a Bryce Canyon National Park checkpoint](/cs/groups/public/@uprr/@corprel/documents/digitalmedia/img_uprrm_natparks_phys_2627.jpg)

A park ranger assists visitors at a Bryce Canyon National Park checkpoint, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

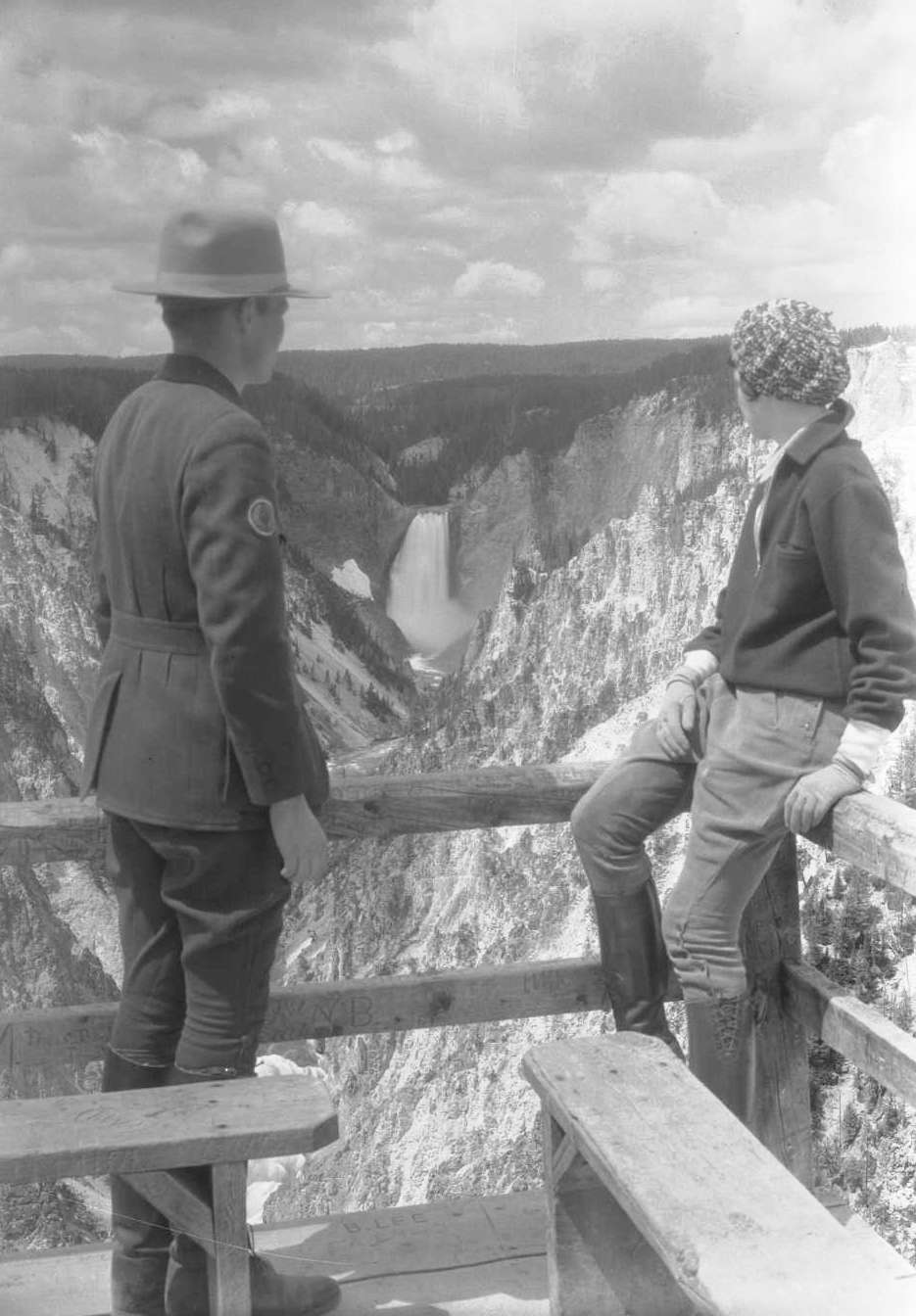

Ranger Frank Sissby and Julie Pressen of Chicago, Illinois, view the Lower Falls of the Yellowstone River and Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone from Artist's Viewpoint at Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

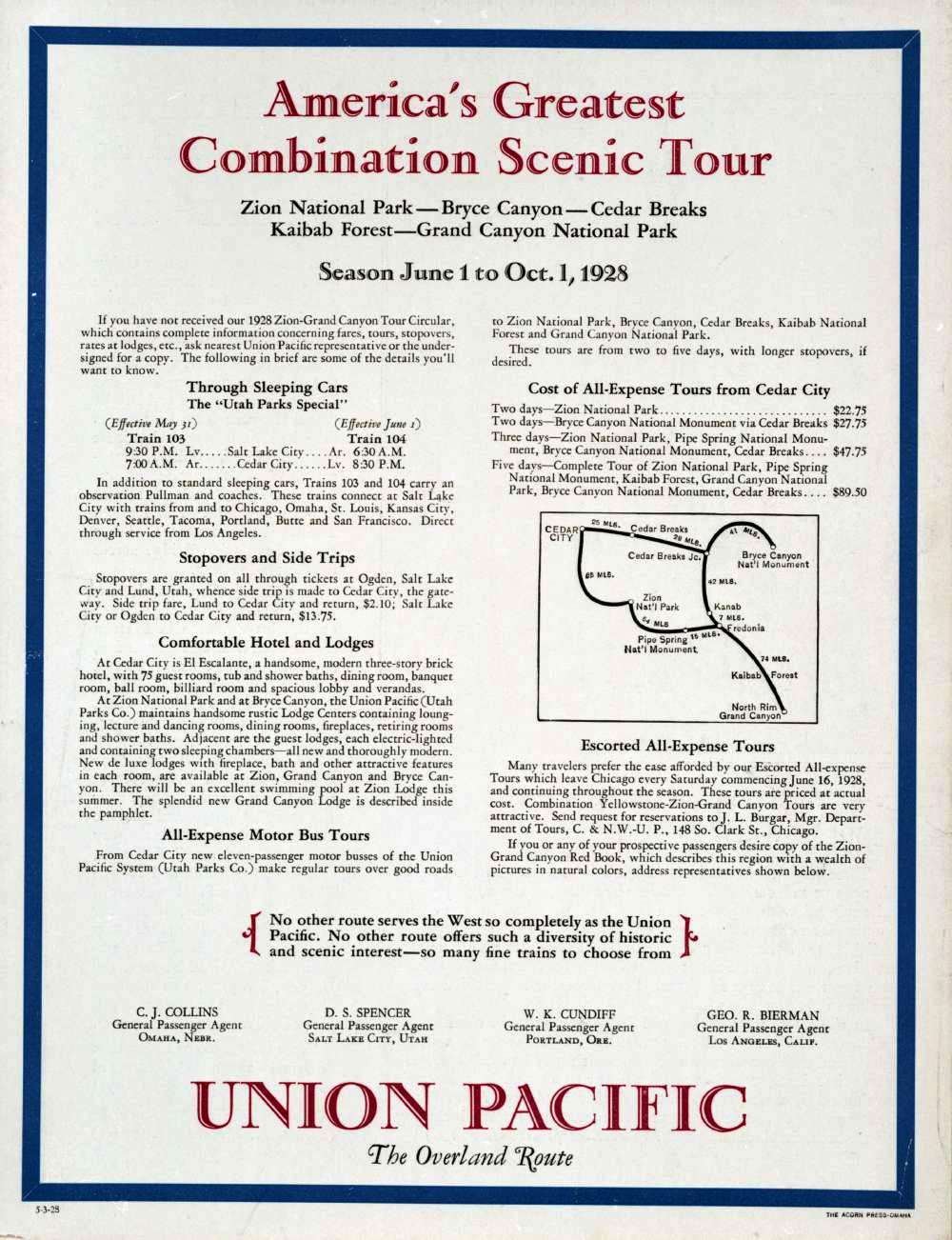

Union Pacific Railroad Overland Route advertisement for "America's Greatest Combination Scenic Tour" to Zion National Park, Bryce Canyon, Cedar Breaks, Kaibab Forest, and Grand Canyon National Park for the June 1, 1928, to October 1, 1928 season, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

Pictured left to right, Eivind Scoyen, first superintendent of Zion National Park, Angus Woodbury, first ranger naturalist of Zion National Park, and Schieffer look down into valley from edge of rock on a Bridge Mountain hike, Nevada, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

Walter Ruesch, Elsie Baer, Gertrude Grant, Lola Jackson and Vincent Hunter, Union Pacific Railroad photographer, travel on horseback through narrows at Zion National Park, Utah, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

![[At Zion National Park, a Navajo woman demonstrates traditional rug weaving techniques, Union Pacific Museum Collection.] At Zion National Park, a Navajo woman demonstrates traditional rug weaving techniques](/cs/groups/public/@uprr/@corprel/documents/digitalmedia/img_uprrm_natparks_phys_2243.jpg)

At Zion National Park, a Navajo woman demonstrates traditional rug weaving techniques, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

Yellowstone National Park “buffalo run,” c1924, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

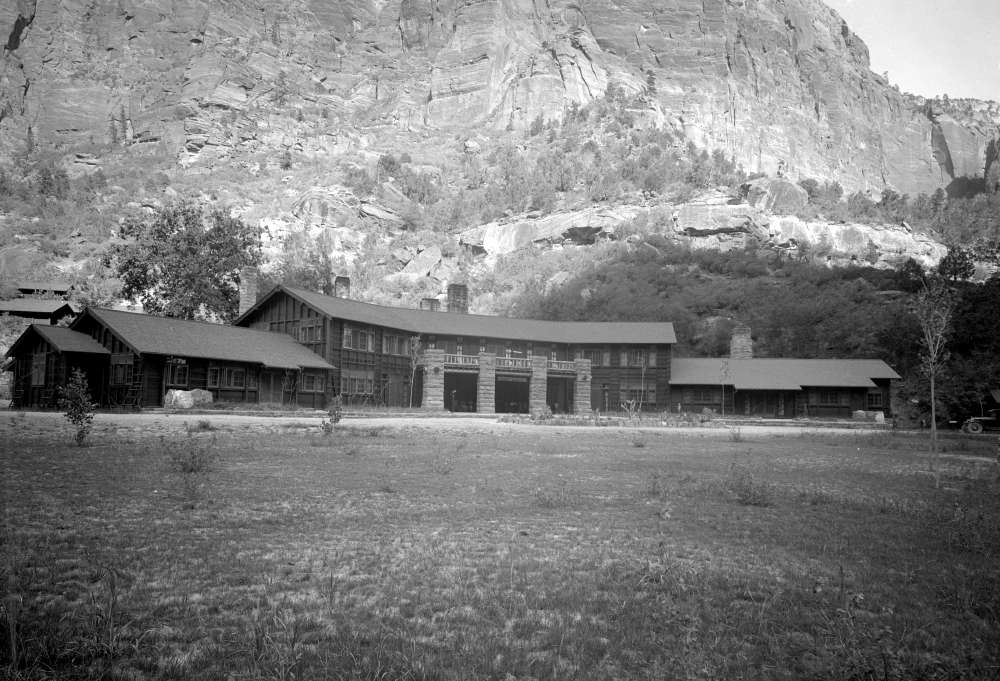

Zion Lodge, completed 1925. Its native sandstone pillars echoed the surrounding vertical canyon walls, and its classic framing-out styled walls mirrored Zion National Park's history as a former Mormon settlement, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

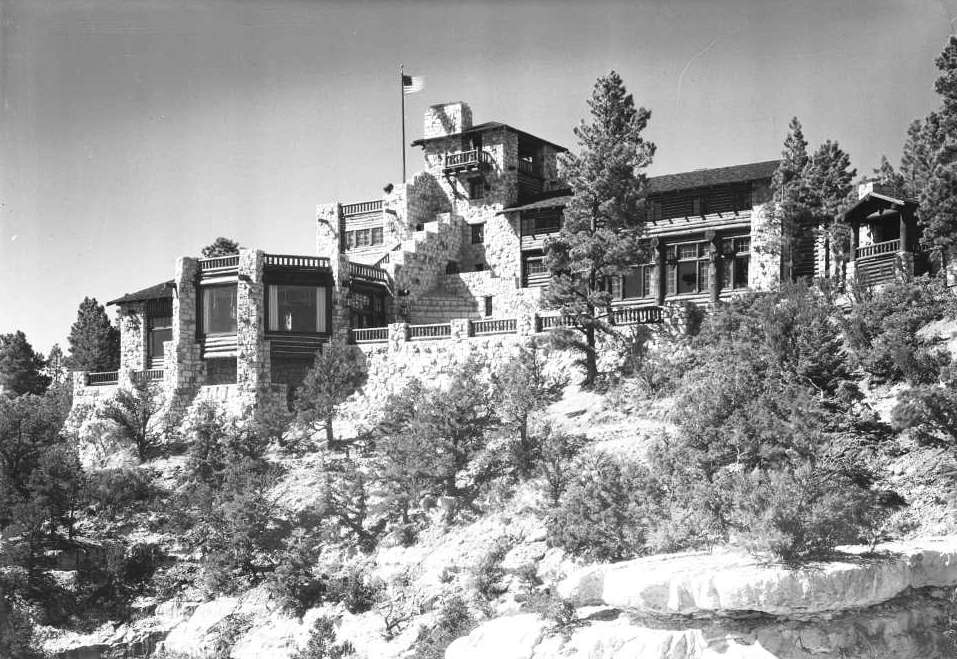

Grand Canyon Lodge was perhaps Gilbert Stanley Underwood's most ambitious national parks project. Completed in 1928, the limestone and wood lodge was built right into the North Rim of the canyon wall as though it were part of the landscape itself. While it was an example of classic Underwood rustic design, it featured prominent southwestern themes that matched the buildings, such as the El Tovar Hotel at the South Rim built by architect Mary Colter for the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, Union Pacific Museum Collection.

-

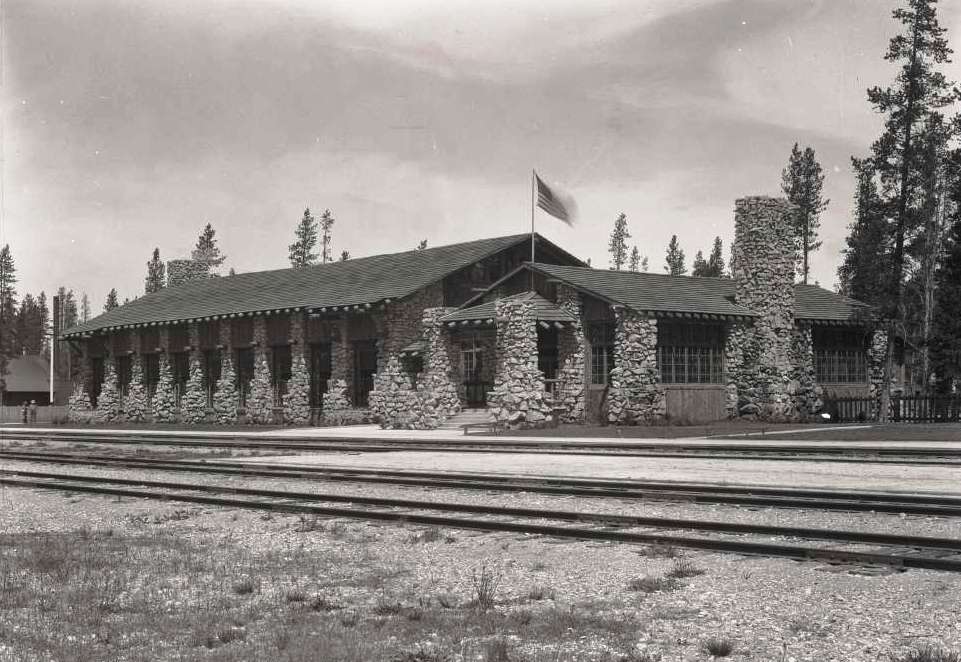

Although not technically a lodge, the West Yellowstone Dining Hall was celebrated as a triumph of rustic design. Completed in 1925, it was built of local rhyolite stone, local peeled and unpeeled logs, and red fir bark slab siding, Union Pacific Museum Collection.