The Railroad and Sun Valley

Creating a Destination.

Sun Valley, America’s first winter destination resort, appeared near the end of the Great Depression. As the number of vacationers increased, railroads hoped to boost declining ticket sales by encouraging travel to exotic locations accessible only by rail. Travel always requires time and money, both in short supply for most Americans during the 1930s. As a result, the first guests at Sun Valley were white, wealthy, and blessed with ample leisure time. Sun Valley’s success, and the country’s economic recovery, began to draw more middle-class tourists to the ski slopes. The Challenger Inn was constructed to provide more affordable accommodations.

Sun Valley, Idaho, circa 1939. Union Pacific Collection.

The Rising of Skiing as Sport in America

Union Pacific brochure cover for Sun Valley featuring American ski racer Gretchen Fraser in Union Pacific ski attire. Fraser won both a gold and silver medal in the 1948 Winter Olympics and was elected to the U.S National Ski Hall of Fame in 1960. She and her husband retired to Sun Valley, Idaho. Union Pacific Collection.

Originating in Scandinavia, skiing spread throughout Alpine Europe. The sport was especially popular in Germany and Austria, where American travelers experienced the thrill of flying down snow-covered mountain slopes. For more than a century, some Northern European immigrants used cross-country skiing to get around in America’s snowier regions. Yet the country had few ski areas and only a handful of collegiate ski teams by the 1920s. After the 1932 and 1936 Winter Olympics interest in the sport grew. As ski technology improved and traveling up the mountain became easier—using rope tows—more Americans headed for the hills. By 1936, the U.S. government reported there were 100,000 skiers in the country. This fact encouraged Averell Harriman, then Chairman of the Board for Union Pacific, to pursue his dream: creating a new kind of American resort destination for railroad travelers.

The Development of Sun Valley

Chair lift prototype in the Omaha, [NE] Shops, designed by mechanical engineer Jim Curran. Union Pacific Collection

Averell Harriman’s father, railroad tycoon Edward Henry (E.H.) Harriman, gained control of the bankrupted Union Pacific Railroad in 1898. He “worked his magic, transforming the railroad into a well-built, efficient operation.” By the time his son Averell became Chairman of the Board in 1931, Union Pacific passenger revenues had nosedived because of the Great Depression. Hoping to recover these losses, Averell Harriman did two things. He developed faster passenger trains and created somewhere new and exciting to go: “an exclusive winter sports resort which will capture the interest of all America.”

Harriman hired Austrian skier Count Felix Schaffgotsch to locate the best place for his new resort. After extensive travels through the western United States, the Count was directed to Ketchum, Idaho. Ketchum was an old mining town on a Union Pacific spur line in the Wood River Valley. It sat amidst the remote mountains of central Idaho. Schaffgotsch remarked, “This contains more delightful features than any other place I have seen in the U.S., Switzerland, or Austria for a winter sports center.” And he sent several telegrams to Harriman: “perfect place, any number excursions… Ideal snow and weather conditions... It’s ski heaven”; “this without doubt is the perfect place.”

Schaffgotsch’s discovery appealed to Harriman. He had worked in Idaho as a young man laying track for Union Pacific. After some initial skepticism, an in-person visit convinced Harriman that they had found the right place. “I fell in love with the place then and there,” Harriman said. Harriman soon purchased 4,000 acres of ranch land from the Brass family. Within four years, the site was transformed into Sun Valley. It boasted the luxurious Sun Valley Lodge, the more affordable Challenger Inn (providing middle-class tourist accommodations), and a unique chair ski-lift. The ski-lift was designed at Union Pacific Omaha headquarters and used for the first time at the resort.

Recognizing Skiing in a Disputed Landscape

First encountered by the railroad in the 1860s during the construction of the first transcontinental railroad, the Shoshone sometimes allied with the new railroad despite the ongoing disruption to their communities. Union Pacific employed Shoshone from the Ft. Hall reservation and entered into an employment agreement with Chief Tendoy in the 1920s providing jobs and training tribal members.

Long before Sun Valley, the Wood River Valley area was inhabited by the continents First Peoples. The Shoshone-Bannock followed migratory herds, harvested wild plants, and lived their lives for thousands of years on the land.

Once European settlers began moving westward along the nearby Oregon Trail in the 1840s, conflict over the land erupted with Anglo settlers removing and displacing indigenous inhabitants. By 1868, in the Fort Bridger Treaty, the Shohsone had endured two decades of warfare pursued by settlers and the U.S. government, and the tribes were confined to the Fort Hall Reservation. Today the Shoshone-Bannock people (as part of the five Federally recognized Tribes of Idaho) have an important, rapidly growing impact on Idaho's economy. As sovereign nations, these tribes have their own governments, health and education services, police forces, judicial systems, economic development projects, gaming casinos and resorts, agricultural operations, retail trade and service businesses, cultural and social functions, and other important regulatory activities. Providing these services creates significant economic and social impacts not only on the Indian reservations, but also in the communities surrounding them. Combined, the five tribes of Idaho are contributing to the economic and social health of the State of Idaho.

In what might have been a nod to the land’s original inhabitants, or perhaps for the publicity value and as a tourist attraction, the Sun Valley Resort often featured native people as entertainers during stage shows and at the rodeo. Because the resort catered to and was enjoyed by mostly white European descendants—established on what were once tribal lands, some historians suggest that tourism itself might be viewed as a type of colonizing conquest.

Ski Culture

Harriman’s familiarity with European ski culture probably gave him the notion that a winter resort could be successful in America. “I thought that was something we should develop in the West,” he said. Hoping to draw on the European model, Harriman hired Schaffgotsch, an Austrian nobleman and gifted skier, to act as an expert on the European ski industry and locate an appropriate site for the resort.

Since Austria had become the best place to learn downhill skiing, Harriman also relied on the Count to add authentic European elegance by hiring the best instructors to staff the Sun Valley Ski School. For the initial 1936-37 season, the Count brought on board six Austrians: Hans Hauser, Joseph Benedikter, Franz Epp, Alfred Dingl, Josef Schwenighofer, and Roland Cossman—a wise choice at that time. “In America’s new consumer-oriented culture, European ski instructors became expert commodities in high demand. They emerged as minor celebrities.” Harriman used the instructors to publicize skiing and highlight the refined European flavor of the new Sun Valley experience.

Another way Harriman incorporated European influences was through his desire to construct a small, rustic lodge “to imitate Swiss and Alpine ski villages.” But he soon became convinced that a large, spectacular resort hotel would attract even more tourists. Architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood designed the $1.5 million Sun Valley Lodge, incorporating a mix of “Art Deco designs and anything reminiscent of the Union Pacific’s streamliners.” When Harriman approved construction of the Challenger Inn in 1937, he asked Underwood to design “something like a Tyrolean* village.” Eventually, the Inn and its surroundings became such a “perfect replica” of a European town, it was used as a movie set for the 1937 romantic comedy, I Met Him in Paris. (*Tyrolean meaning a region of the eastern Alps in western Austria and northern Italy)

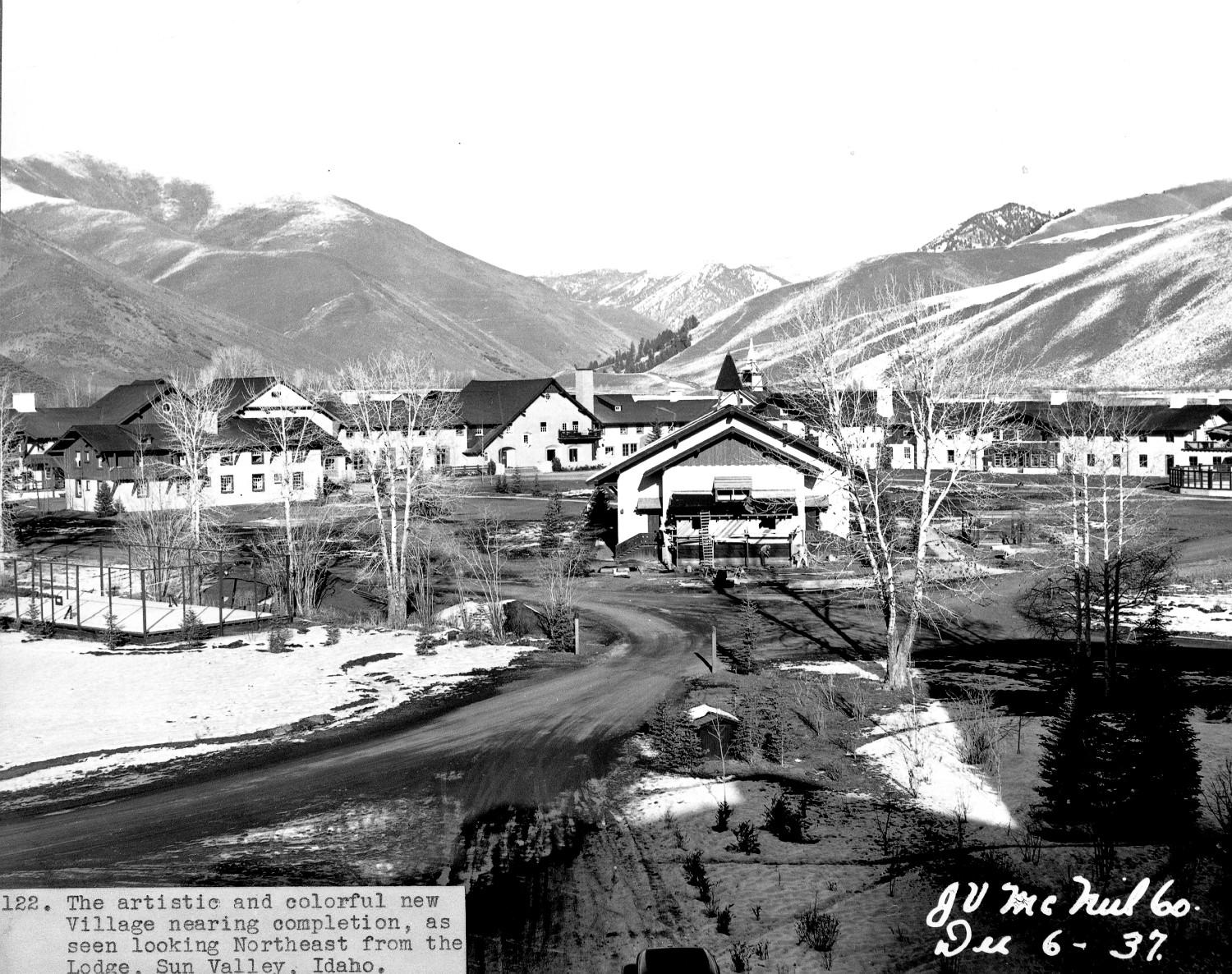

"The artistic and colorful new village nearing completion as seen looking northeast from the lodge, Sun Valley, Idaho, December 6, 1937." [taken from caption] Image taken by J.V. McNeil. Union Pacific Collection.

Nazis in the Valley

Sun Valley ski instructors pose outside of the lodge wearing their uniforms reminiscent of Alpine ski lodges in Germany, c1937.

Harriman’s choice of Austrian ski instructors brought consequences once WWII began in 1939. Several reliable sources suggest that Count Schaffgotsch and some of his hand-picked instructors at Sun Valley’s ski school were Nazi sympathizers.

British actor David Niven befriended the Count and spent much time with him in both Europe and Sun Valley. Referring to Schaffgotsch, Niven said, “he spent hours extolling the virtues of Hitler, sympathizing with his problems and enthusing over his plans…. Felix said he was bringing over a dozen good ski instructors from near his home in Austria, …all Nazis, too.”

Eventually, the Count’s outspoken support for Hitler seems to have discouraged Harriman from putting him on the payroll for the 1938-39 season. When Schaffgotsh inquired about work at the resort via telegram from Austria, Harriman replied, “this winter’s organization completed…. therefore no position open.” The Count’s position was filled by another Austrian skier, Freidl Pfeifer. Schaffgotsch later joined the German Army and disappeared fighting on the Russian front.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, FBI agents descended on Sun Valley, an international hub with a high concentration of staff and guests from European areas affected by the war. Thus, Pfeifer, Hans Hauser (head instructor at Sun Valley’s ski school), and several other Austrian nationals were arrested, interrogated, and placed in internment camps for various lengths of time. Upon release, many enlisted in the American armed forces, most notably the Tenth Mountain Division, one of the most highly decorated units in the European theater. But Hans Hauser chose to remain in a prisoner of war camp until war’s end.

As the war ramped up, Harriman became more involved in serving Roosevelt’s administration, “acting as ambassador to Great Britain and the Soviet Union, and attending nearly every important meeting involving world leaders, including the Potsdam and Yalta Conferences.”

The war also took a toll on Sun Valley. As tourist numbers declined, Harriman decided to close the resort in 1942, offering the facilities for government use. In 1943, the Sun Valley Lodge was commissioned as a Naval Convalescent Hospital. “I offered to do it….it was the right thing to do,” Harriman recalled. The Navy spent two and a half years at Sun Valley, providing treatment to almost 7,000 men, veterans from the war in the Pacific.

Hollywood at Sun Valley

March 13, 1939, film star Gary Cooper and Mrs. Cooper prepare to board Union Pacific's "City of Los Angeles." The Coopers were frequent guests at Sun Valley. Union Pacific Collection.

As Ivy League graduate, railroad owner, international investment banker, and one of the country’s wealthiest men, Averell Harriman was already connected to America’s privileged class. And his political and diplomatic service during four presidential administrations put him in touch with some of the world’s richest and most powerful people. It’s no surprise, then, that from its opening Sun Valley boasted a roster of notable people. Names such as Pabst, du Pont, and Rockefeller graced the guest list for the resort’s grand opening in 1936, a glittering affair including people from Broadway, Wall Street and Fifth Avenue in New York, as well as celebrities from Hollywood.

David O. Selznick, Claudette Colbert, Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, Marilyn Monroe are just a few of the famous faces who appeared on the ski slopes. In fact, Selznick--a film producer, screenwriter, and studio executive (a close friend of Harriman’s) --volunteered to conduct an extensive advertising campaign for Sun Valley in Hollywood, thereby drawing even more big names to the resort. Groucho Marx, Cyd Charisse, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Charlton Heston, and Telly Savalas were among the resort’s notable visitors.

Sun Valley also attracted the famous American author Ernest Hemingway. Harriman “had worked out a deal with the writer giving him free residence at the Lodge as long as Hemingway socialized with the guests.” Much of Hemingway’s novel For Whom the Bell Tolls was written at the Lodge, and soon the author bought a house in nearby Ketchum, where he lived until his death in 1961.

Harriman’s political connections brought many of Washington’s—and the world’s—leaders to Sun Valley. The Shah of Iran was a frequent visitor, and at various times, the resort played host to U.S. Presidents Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy and many members of his family, and Gerald Ford.

End of an Era

Union Pacific's Sun Valley, Idaho poster features collage of activities such as skiing, skating, sun bathing, and more. Union Pacific Collection.

For several decades after WWII, Sun Valley continued to experience phenomenal success. But times were changing. New ski resorts appeared throughout the West. Actively encouraged by Harriman (and with some sites developed by former Sun Valley ski instructors), places like Aspen, Alta, and Deer Valley drew away customers.

Americans also began travelling in new ways. Airlines offered more flights to more places at reasonable prices, and construction of the interstate highway system encouraged tourists to take their own cars. Pre-WWII figures indicate that Sun Valley brought UP an additional $250,000 in annual ride revenues. While Sun Valley still attracted record numbers after the war, increased competition from other modes of travel sent passenger profits into steep decline.

Harriman, too, was growing more distant from the resort he had created and nurtured. During WWII, he spent much time in Europe, working for the Roosevelt administration. Then, when President Truman appointed him Secretary of Commerce in 1947, Harriman was required to cut all ties with the business world, and he resigned as Union Pacific’s Chairman of the Board. From this point forward, Harriman’s diplomatic and political duties took up most of his time. Without his support and hands-on care, Sun Valley seemed a less-attractive investment to the remaining railroad executives, who kept keen eyes on the bottom line. Eventually, Union Pacific decided to cut their losses, and sold Sun Valley to Bill Janss, a resort developer, in 1964.

Janss invested millions of dollars in renovations and upgrades, opened the resort year-round, and encouraged new residents by developing houses and condominiums for permanent occupancy. For those people, Sun Valley offered a lifestyle rather than a glamorous vacation.

Ready to move on after his successful revival of Sun Valley, Janss sold the resort to Earl Holding, a Utah businessman, in 1977. The Holdings have continued development and expansion, and today Sun Valley and the surrounding area remain one of America’s top tourist attractions with a surprising railroad past.